In the early 1940s, Felipe Cossio del Pomar arrived in San Miguel de Allende at a moment when the city was beginning a quiet but lasting transformation. Long valued for its strategic location, colonial architecture, and strong civic identity, San Miguel was also emerging as a place where artists, educators, and independent thinkers could build meaningful institutions outside Mexico City. Cossio del Pomar, a painter, critic, and cultural organizer, recognized this potential early. His vision found a physical home in El Rancho Atascadero, a historic property at the edge of the city that he transformed into a campus for the Escuela Universitaria de Bellas Artes. In later decades, the property would pass into the care of the Maycotte family. What follows is Cossio del Pomar’s own account of El Atascadero, presented here as a continuous narrative that reflects his observations on place, purpose, and the role of culture in San Miguel de Allende.

El Rancho Atascadero

A letter written by Felipe Cossio del Pomar

In Mexico, I felt at home. Small difficulties never diminished my larger sense of purpose. Everything seemed to resolve itself calmly, through solutions that were usually straightforward. The sale of La Ermita was, above all, a sentimental sacrifice, but it cleared the way for what came next.

That was when El Rancho Atascadero entered my life.

Pepe Ortiz, a bullfighter and the owner of the ranch, helped me solve the growing space constraints faced by the School. His Marian devotion had led him to rename the property Cañada de la Virgen, but names with history, no matter how unappealing they may seem, are difficult to change. People continued to call the place Atascadero, the name long associated with the ravine bordering the upper part of the city.

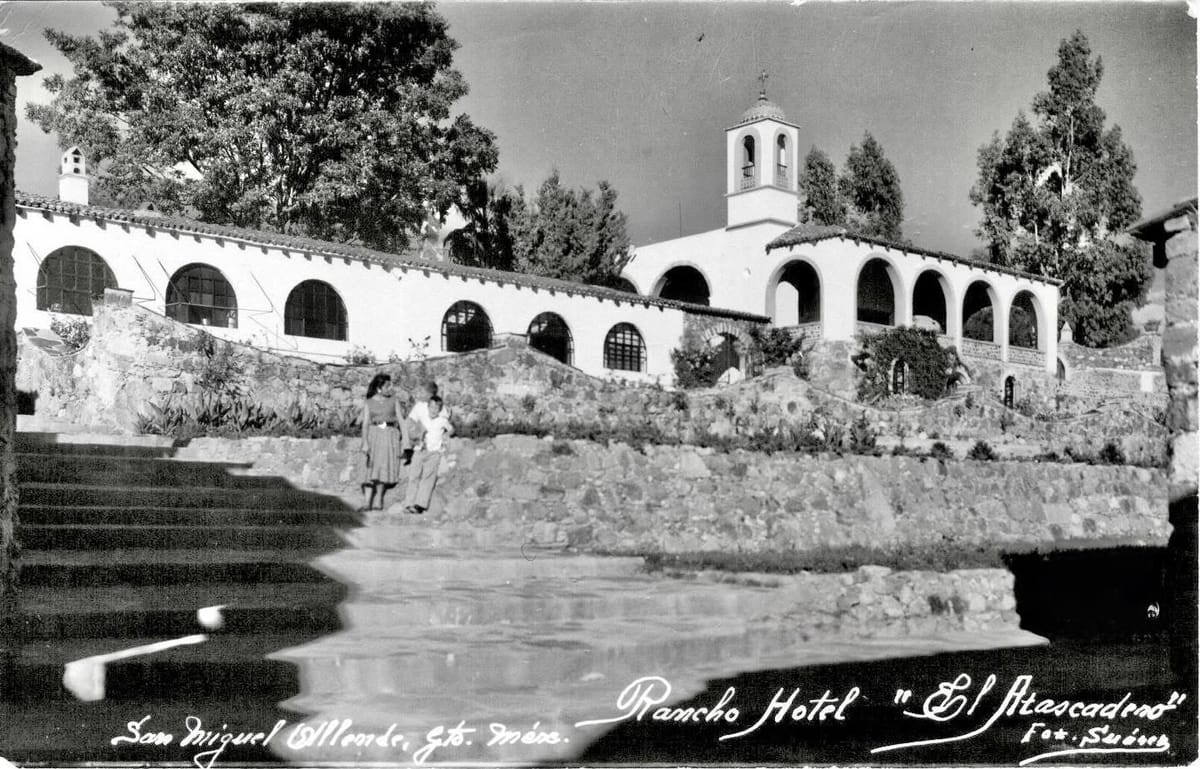

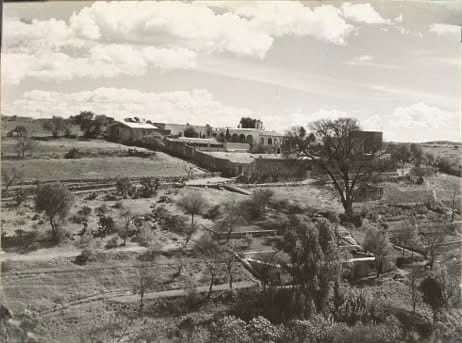

A stone wall marked the boundary between the ranch and Santo Domingo Street. Inside the enclosure, the land rose gently uphill, spreading across rolling hills planted with ash trees, poplars, and small vegetable plots. Streams fed by natural springs appeared throughout the property. Shaded areas alternated with the soft, filtered light that I admired from my first day in San Miguel de Allende. Along the paths and hillsides, pinks, greens, and warm earth tones formed naturally shifting compositions. It was a place well suited for reflection and creative work.

Before it came into my hands, the ranch had already lived several lives. Pepe Ortiz had purchased it from the heirs of Monsieur Hipólito Chambon, a Frenchman whom the government of Porfirio Díaz had tasked with promoting silk production in Mexico. Chambon considered San Miguel de Allende an ideal location for the project and covered the Atascadero with mulberry trees, whose heart shaped leaves are the preferred food of silkworms. The planting extended beyond the ranch itself, filling streets and plazas throughout the city. I still saw many of these trees at Atascadero, casting dense shade over small reservoirs that Chambon had built to raise trout, a pleasure aligned with his culinary tastes.

This place of quiet abundance became ours.

The first improvement I made was to build a cobblestone road, lined with trees and wide enough for automobiles, connecting Santo Domingo Street directly to the main house. The road began at a monumental entrance. My nostalgia for Cusco led me to recreate, with only minor changes, a seventeenth century colonial gateway from that city. It was a personal gesture, a way of carrying other geographies and memories into this landscape.

Speculation never crossed my mind when I acquired El Atascadero. Located within a city undergoing steady urban growth, its potential commercial value was obvious. But my concern was the School, along with the satisfaction of improving a place that was already inherently beautiful. The goal was to adapt the ranch to serve as a true academic campus. Motels were not yet a concept in Mexico, and even if they had been, I would have rejected such a use.

Drawing inspiration from certain educational institutions in the United States, I envisioned a campus where academic life and individual initiative could coexist naturally. I converted a large water reservoir on a hill into an Olympic size swimming pool, complete with changing rooms and showers. Around the entrance courtyard, I built eight apartments with studios, bedrooms, and bathrooms. The height of the original walls allowed for duplex style interiors, reminiscent of my studio in Paris. Additional spaces included a large communal dining hall, kitchens, gardens, stables, pens, chicken coops, and facilities for more than twenty cows, since the milk produced on site was insufficient for the growing population.

For the upper part of the property, I chose to reforest with Peruvian pepper trees, known as molle, rather than mulberries, since my objectives differed from those of Monsieur Chambon. According to historical accounts, a viceroy once ordered that seeds brought from Peru be scattered along travel routes throughout New Spain. The molle adapted quickly, taking root in rocky crevices, wetlands, and even cold high elevations. Over time, roads across the region became marked by these trees with their distinctive red clusters.

As construction progressed, the ranch took on its new form. Floors were laid with locally quarried stone veined in sepia and violet, a material that San Miguel’s stonemasons work with exceptional skill. I had first admired this stone in Mexico City, at the home of engineer Gonzalo Robles, former director of the Bank of Mexico, whose generosity matched his intellectual depth. I used the stone extensively at both La Ermita and Atascadero, as the quarries lay just over a kilometer from the city.

That year, rising above the group of buildings, the tiled dome of the chapel built by Pepe Ortiz stood out more brilliantly than ever. It reflected a traditional priority: care for the soul before comfort of the body.

As my friend Salvador Ugarte took pleasure in sharing his collection of Renaissance engravings, I enjoyed showing the ranch to the many visitors who came to San Miguel during the celebration of the city’s four hundredth anniversary in 1942. Among them were friends whose presence I still recall with gratitude.

Without spectacle or commercial intent, El Atascadero ceased to be merely a ranch. It became a place for study, collaboration, and daily life, shaped by landscape, architecture, and shared purpose.

Felipe Cossio del Pomar’s account of El Atascadero offers a clear window into a formative chapter of San Miguel de Allende’s cultural history. His work reflects an approach grounded in stewardship rather than speculation, and in education rather than display. El Atascadero stands as an early example of how thoughtful development, respect for place, and long term vision helped shape the San Miguel that continues to draw artists, residents, and visitors today.

Sources and Credits

Primary Text

Cossio del Pomar, Felipe. Iridiscencia: Crónica de un centro de arte. Consejo Editorial, Gobierno del Estado de Guanajuato, 1988.

Historical Context

Proyecto Cultural Felipe Cossio del Pomar.

Instituto Allende and Escuela Universitaria de Bellas Artes archives, San Miguel de Allende.

Images

Entrance to El Rancho Atascadero on Santo Domingo Street. Archivo Cossio del Pomar.

El Rancho Atascadero, 1941. Gela Archipenko Archive, Smithsonian Institution.

Road leading to El Rancho Atascadero. Kiosco de la Historia, San Miguel de Allende.